In Search of the Promised Tomatoland, Part 1: The Problem

August 19, 2011

Editor’s note: This is the first in a two-part series based on a recent CUESA panel featuring (from left to right below) Nigel Walker of Eatwell Farm, Larry Jacobs of Del Cabo, Barry Estabrook, author of Tomatoland, and Damara Luce of Just Harvest USA.

“What you see on the screen is not a tomato,” Barry Estabrook told a small crowd recently, as he pointed to a spherical red fruit on a television screen in the Ferry Building’s Port Commission Hearing Room. “It’s a Florida-grown industrial product.”

Estabrook was in town to promote his new book, Tomatoland, which is the culmination of several years of research into the underworld of the Florida tomato industry and the people (i.e. workers) who make it possible.

One third of the tomatoes eaten in the US come from Florida, and the bulk of those are grown in the winter near a town called Immokalee. Like most of modern agriculture, the industry is controlled by a small number of very large farms.

Despite their industrial size, Florida tomato growers, says Estabrook, have several significant obstacles. First, the soil there is essentially sand (“not sandy loam, not sandy soil, but pure sand, no more nutrient rich than the stuff vacationers like to wiggle their toes into on the beaches of Daytona and St. Pete,” he writes in the book). Combine that with a warm, damp environment where pests and funguses thrive, and you can see why the Florida growers rely on an abundance of synthetic nitrogen fertilizer and as much as eight times the pesticides (110 different kinds, including methyl bromide) as tomato farmers in California.

Despite their industrial size, Florida tomato growers, says Estabrook, have several significant obstacles. First, the soil there is essentially sand (“not sandy loam, not sandy soil, but pure sand, no more nutrient rich than the stuff vacationers like to wiggle their toes into on the beaches of Daytona and St. Pete,” he writes in the book). Combine that with a warm, damp environment where pests and funguses thrive, and you can see why the Florida growers rely on an abundance of synthetic nitrogen fertilizer and as much as eight times the pesticides (110 different kinds, including methyl bromide) as tomato farmers in California.

With that much pesticide on the plants, one might hope, for the workers’ sake, that the tomatoes could be picked by machines. Not so. In fact, a great deal of Tomatoland is devoted to the plight of the Immokalee workers, a number of whom Estabrook spent time interviewing and getting to know.

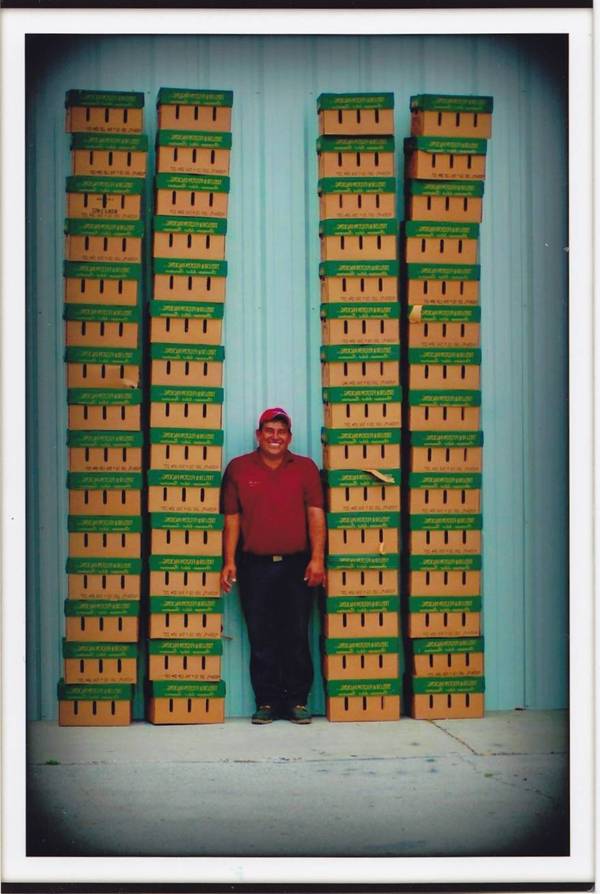

That’s why, when Estabrook told the crowd, “The men and women who pick tomatoes and grow them probably have the worst legal job in the US,” they were prone to believe him. And he had ample evidence of the fact. He pointed to a photo of a worker standing under a literal tower made from 1500 pounds of tomatoes stacked in boxes (see photo at the right). The pay for picking all those boxes, often in staggering heat? A measly 17 dollars. Estabrook then showed photos of the average worker’s living quarters: a trailer occupied by 10 men with an airplane lavatory-sized bathroom and a barely functional kitchen – for the high price of $2,000.

Then he shared a photo of a little boy named Carlitos, who had been born without arms or legs. Carlitos’ mother was one of a handful of women who were told they couldn’t stop working with pesticide-laden plants (in some cases leaving the fields literally wet with the chemicals) if they wanted to keep their trailers.

These conditions are bad enough on their own, but they pale in comparison to those faced by people brought to Immokalee to engage in forced labor by human traffickers. According to Estabrook, seven major slavery cases – involving 1200 people – have been brought to justice in Florida in the last 15 years. “It’s slavery, pure and simple,” he told the crowd. “We’re talking people bought and sold, shackled in chains, and locked in the back of produce trucks. People being beaten for not working hard enough or for trying to escape.”

These conditions are bad enough on their own, but they pale in comparison to those faced by people brought to Immokalee to engage in forced labor by human traffickers. According to Estabrook, seven major slavery cases – involving 1200 people – have been brought to justice in Florida in the last 15 years. “It’s slavery, pure and simple,” he told the crowd. “We’re talking people bought and sold, shackled in chains, and locked in the back of produce trucks. People being beaten for not working hard enough or for trying to escape.”

Working for Change

On a less gloomy note, Estabrook also talked about his time with the Coalition for Immokalee Workers (CIW), a 4,000-member group of organizers that has been working for nearly two decades to improve the lives of tomato workers. He was joined on the panel by Damara Luce of the Oakland-based organization Just Harvest USA. Luce moved to Immokalee in 1999 as an AmeriCorps volunteer and stayed through much of the 2000s after becoming involved with the CIW. As she put it, she “fell in love with this group of workers” and was inspired by the fight to engage companies at every level of the corporate food chain.

When Luce arrived in Immokalee, the pay rate for picking a 35-pound bucket of tomatoes was still hovering below 50 cents – exactly as it had been since the 1970s – making abject poverty a consistent reality there. “They said, ‘We’re not going to take it anymore,’” Luce told the audience. “‘We don’t know exactly how we’ll fight it, but we want to try.’”

Through the 90s, the CIW focused on putting an end to physical beatings in the field. In the decade since, they have expanded their reach, working with campus organizers, faith-based groups, and others in the food justice movement to create buy-in for their Campaign for Fair Food at nearly every level of the food supply chain. The campaign began with “Boot the Bell,” a boycott of Taco Bell on university campuses led by students around the nation, many of whom, thanks to anti-sweatshop organizing, had recently become aware of supply chain responsibility. The campaign has since grown to include all the major fast food chains, food service companies, and (as of late 2010) the big tomato growers – all of whom have signed on to something called the Fair Food Agreement.

Through the 90s, the CIW focused on putting an end to physical beatings in the field. In the decade since, they have expanded their reach, working with campus organizers, faith-based groups, and others in the food justice movement to create buy-in for their Campaign for Fair Food at nearly every level of the food supply chain. The campaign began with “Boot the Bell,” a boycott of Taco Bell on university campuses led by students around the nation, many of whom, thanks to anti-sweatshop organizing, had recently become aware of supply chain responsibility. The campaign has since grown to include all the major fast food chains, food service companies, and (as of late 2010) the big tomato growers – all of whom have signed on to something called the Fair Food Agreement.

The Fair Food Agreement has made a number of basic working conditions much better for tomato pickers: growers must now provide shade tents and health and safety trainings, and must have a grievance process in place. And, most importantly, some workers are receiving one penny more per pound — a difference that may sound small, but can result in as much as $30 more per day.

But the campaign isn’t over, and the next frontier is convincing supermarket chains to sign on to the agreement. According to Damara, “Even though all the growers are participating — and the extra penny per pound from fast food and food service companies is getting passed down in the form of a wage increase — if you’re picking for [a major grocery store like] Walmart, Ralphs or Trader Joe’s, you’re not going to get that pay increase.”

Learn more about the CIW’s efforts to reach major grocery stores here. And stay tuned for In Search of a Promised Tomatoland, Part 2: The Alternatives.

Topics: Agribusiness, Labor, Talks