A Complex Cup

Brie Mazurek, CUESA Staff

February 1, 2013

At the farmers market, you can meet the farmer who grew your carrots, talk to them about their growing practices, and feel confident that your food dollars are going directly to the farm. But the path coffee travels from farm to cup is much more mysterious. How can you feel good about the businesses you’re supporting with your coffee dollars and ensure that farmers thousands of miles away are receiving their fair share?

Roasters and experts explored these questions at a “Coffee and Sustainability” panel discussion hosted by CUESA at the Ferry Building on January 21. “The farmer and consumer are most important [in the supply chain], and they’re the most disconnected geographically and emotionally,” said Colby Barr, co-owner of Verve Coffee Roasters in Santa Cruz.

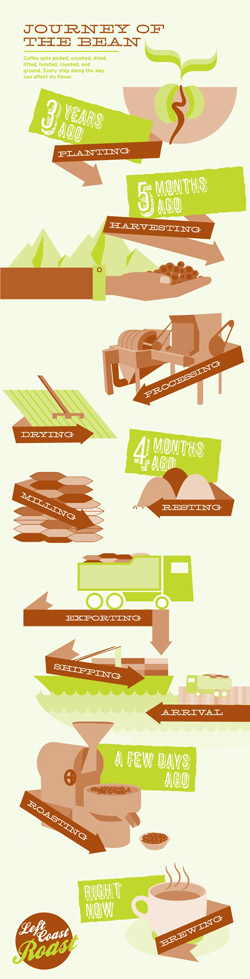

Most US coffee drinkers have little concept of where their $3 goes after they get their artfully brewed cappuccino. “One of the perplexing facts about coffee is that it is primarily grown in countries that have developing economies, and it is primarily consumed in countries that have developed economies, which sometimes presents moral dilemmas,” said Hanna Neuschwander, author of Left Coast Roast, who moderated the discussion. The United States is the world’s top consumer of coffee, while the majority of coffee is grown in equatorial countries, with Brazil, Vietnam, Columbia, and Indonesia being the largest producers.

Most coffee farmers are poor, and eking out a livelihood can be difficult for them. Before reaching the consumer, coffee passes through processors, co-ops, brokers, exporters, importers, roasters, and retailers. These intermediaries all take their cut, which leaves only a small piece of the pie for the grower. Like most crops, coffee is seasonal, with the harvest lasting just a few weeks—a fact that may be lost on many coffee drinkers, who rarely see any fluctuation in supply at the café. But its seasonality is acutely felt by many growers who rely on the income from the harvest to sustain them year-round, exposing their families to periods of seasonal hunger. Coffee farming also carries other risks: the trees are sensitive, making farmers especially vulnerable to severe weather and climate change.

Another key factor in the supply chain is the volatile global market. Like wheat and oil, the price of coffee is set by the commodity market, which is dictated less by supply and demand than by the whims of Wall Street. Certification programs like fair trade attempt to bring some stability to farmers by adding a premium to the base commodity price (known as the “C price”), but if the market takes a steep fall, fair trade farmers may still not make a livable income.

Another key factor in the supply chain is the volatile global market. Like wheat and oil, the price of coffee is set by the commodity market, which is dictated less by supply and demand than by the whims of Wall Street. Certification programs like fair trade attempt to bring some stability to farmers by adding a premium to the base commodity price (known as the “C price”), but if the market takes a steep fall, fair trade farmers may still not make a livable income.

Many third-wave coffee roasters, represented on the panel by Barr of Verve and Steven Vick, quality control manager at Blue Bottle Coffee Co., attempt to bridge the gap through direct trade with growers. Roasters generally negotiate a price with the farmer, placing a higher premium on high-quality beans. If a roaster likes a grower’s beans, they might agree to a pay a set price on future harvests (“forward contract”), bypassing the unpredictable commodity market. (While “direct trade” might sound like roasters are importing their beans straight from the farm, intermediaries still play an important role in connecting roasters and growers.)

Finding quality beans can be a challenge, since many growers may not know how to gauge the quality of their own product. “The worst coffee you’ll ever taste in your life is in coffee-producing regions, because they export the good stuff and drink the bad stuff,” said Barr. Both Verve and Blue Bottle practice “cupping” (coffee-speak for professional tasting) with their growers to help educate them on US coffee drinkers’ tastes. “A big part of it for us is to calibrate with the farmers and say, ‘This is what we’re looking for, this is how we roast coffee, and this is what we’re going to pay more money for,’” Vick added. “It really empowers the farmer to know what their quality is so that they can demand the right price.”

Quality doesn’t necessarily translate to sustainability, though, if growers aren’t adequately compensated. Growers can’t invest in more sustainable infrastructure (say, for composting) if they aren’t making enough money to maintain their operation and feed their families.

How can coffee lovers help push the industry toward more environmentally, economically, and socially sustainable practices? “If you love quality coffee, but you don’t know how that money is being spent, you should be asking questions,” said Neuschwander. “If consumers aren’t demanding that information, why would [roasters] spend the time or effort to put it out there?” Some roasters, such as Counter Culture Coffee and Just Coffee, provide detailed information about their relationships and financials online.

And what about labels? From organic to fair trade to Rainforest Alliance to Smithsonian Bird-Friendly, there’s a dizzying array of certifications for coffee drinkers to sort through, and different certifications address different pieces of the sustainability puzzle. “Certification itself isn’t a guarantor of sustainability, but it sets up criteria that move us closer to sustainability,” said Christopher Bacon, an environmental social scientist and co-author of Confronting the Coffee Crisis.

While no certification is perfect, Bacon indicated that Fair Trade offers a model for creating a more democratic global coffee trade. “It’s one of the few certifications that raises the issue of justice in the food system.” He also urged drinkers to look for coffee that is shade-grown, meaning it was grown using agroforestry methods that protect biodiversity and provide edible tree crops for coffee-growing communities.

Blue Bottle’s and Verve’s coffees are mostly certified organic, though they are not certified Fair Trade. Their hope is that the demand for quality will help inspire more transparency and more sustainability throughout the supply chain, as roasters pay higher premiums through direct relationships with growers.

For Barr, sustainability is inextricably linked to economic viability, which is why paying a fair price for high-quality coffee benefits growers, roasters, and drinkers. “To have longevity, you need to have a relationship, and to have a relationship, you have to pay farmers well,” he said.

Look for Blue Bottle Coffee at the Ferry Plaza Farmers Market on Saturdays, Tuesdays, and Thursdays.

Cappuccino photo by Stephen Rees/Flickr. “Journey of the Bean” art from Left Coast Roast.

Topics: Environment, Farmers, Food makers, Talks