Sogorea Te’ Land Trust Reunites Ohlone Land with Indigenous Feminist Stewardship

Selina Knowles, Communications Coordinator

November 3, 2022

For thousands of years, the San Francisco Bay Area has been home to the Ohlone people, the original stewards of this land. Led by urban Indigenous women of the Confederated Villages of Lisjan, one of many Ohlone nations, Sogorea Te’ Land Trust (named after a 3,500 year old Ohlone village) is working to heal the legacies of colonization, genocide, and patriarchy. Through the work of rematriating and restoring ancestral homelands in the San Francisco Bay Area, they are also revitalizing traditional ecology and foodways.

In honor of Native American Heritage Month this November, Foodwise talked with Corrina Gould, co-founder of Sogorea Te’ Land Trust, about returning to traditions in order to reimagine thef future of our relationship with the land and with each other.

Foodwise: Why is environmental restoration so closely tied to Indigenous cultural revitalization?

Gould: If we look at California, California is a new environment that’s been built upon. Everything you see is only about 200 years old, very young. In all of these little pockets of ecology that have been here, there were thriving salmon and steelhead trout that came up these creeks. Imagine just a few hundred years ago, you could drink out of every creek in the Bay Area and that nothing in the Bay was polluted. You had enough. There was an abundance here.

How do we open up these creeks so that they can breathe again? How do we clean them up so our children can play in them again, so that we could plant the plants that are supposed to be there, that actually take out pollution? Doing this ecological work, what we call ecological work now, is really tending to the land the same way that our ancestors had told us to tend to it for thousands of years.

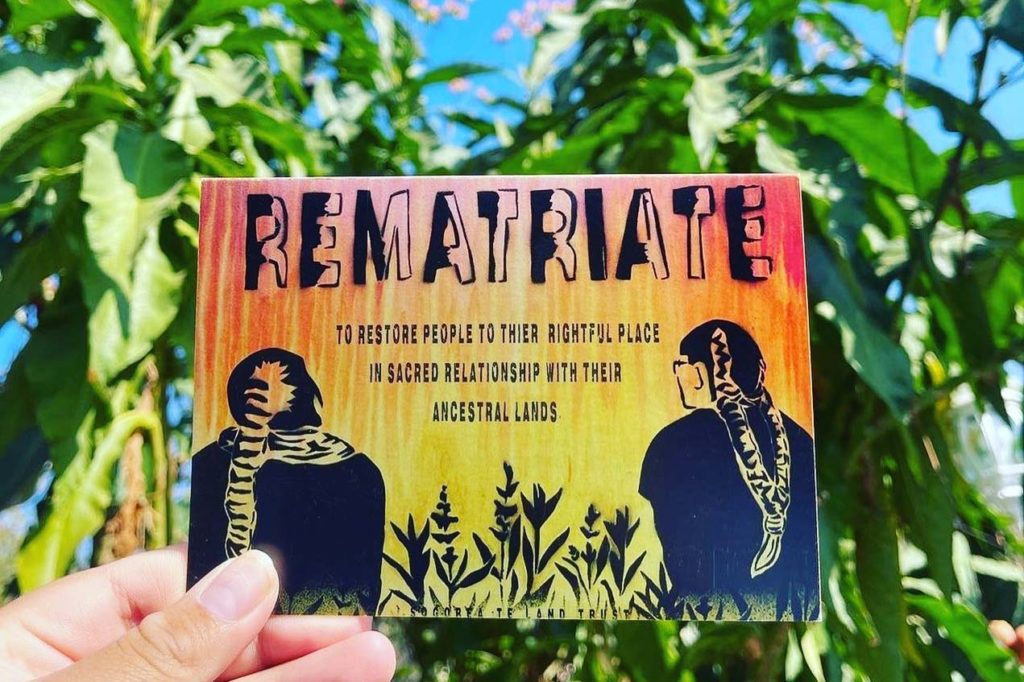

I know a big part of your work is rematriation, so could you describe what rematriating the land means to you?

Rematriation is an Indigenous feminist work. When we look at who’s been in charge of the land over centuries, we know that it’s men. Men were the first settlers, or people that came to other people’s lands. When those things happened, they took away the sacred. Then, they attacked women, took away women’s leadership, and began to desecrate women the same way they desecrated land, by raping, pillaging, and extraction, and taking us out of our leadership roles.

Rematriation is to look at that violence and reimagine our world in a different way. As women, what were our responsibilities before colonization? How has leadership taken place? How do we put ourselves in that frame of mind where we are a part of the land, not apart from the land, and ensure that there’s clean water and fresh air and good soil for the next seven generations?

How are you feeling about the news of the Sequoia Point land return (which restored five acres of the Oakland hills to Indigenous stewardship)?

I’m still in shock about the very first quarter acre of land that we have that was given to us by Planting Justice in Oakland, but this is something on a whole different level. The amazing thing is that Sogorea Te’ Land Trust, the Lisjan people, never approached the city with this idea. They actually came to us. The mayor came to us and said that she wanted to have a conversation and had realized, through a movie called Beyond Recognition, the horrible things that happened on the land.

This has been in process since 2018. It’s something that we recently announced because we wanted to get it right. There are no real mechanisms for cities to give back land, so we were creatively trying to figure this out, not just for Sogorea Te’ and the Confederated Villages of Lisjan, but because we wanted this to be a blueprint for other tribes and other cities to use in order to give land back.

How have you navigated through existing systems that reward privatization of land for profit, while pursuing a vision that is more shared and collective?

The biggest piece of this, and it’s outside of Sogorea Te’, is mostly the tribal work of protecting our sacred site in West Berkeley, one of our oldest burial sites and first village sites along the Bay. It’s very difficult for me to believe that someone can own someone’s burial site or sacred place, and that should never happen. Private land ownership in this country has allowed that to happen by also saying that Native people don’t have the same rights to their cemeteries and sacred places as other people that have come here afterwards.

When we think about land, it’s not about producing something; it’s with the eye towards re-engaging people, teaching young people and people that are outside of our communities about the land that they’re on. Our cultural teachings are about being inclusive and about dreaming together. That’s what Sogorea Te’ Land Trust is about, reimagining and welcoming other people to dream with us about a better future.

On this note of imagining our future, in Sogorea Te’ Land Trust’s vision, when we’re gathering on returned Indigenous land, what kinds of foods are we eating? What food traditions are you seeking to revitalize or bring awareness to?

One of the things that we’re hoping to do is reintroduce California native plants. If you could imagine, in the Bay Area, there were fields of wildflowers. We would harvest those wildflower seeds, and we would eat them and take in all of the protein and nutrients. We’ve heard of chia seed, and it’s kind of blown up. California Native people actually ate tons of seeds.

We’re beginning to look at what those plants are, and consider how to put them in places where we could all enjoy them again. As Lisjan people, we have not had gathering rights in our own territory for over 150 years, which means we can’t go out to parks and look for acorns or mushrooms or these things without special permission or permits. It makes it difficult for traditional foods to come back.

By tending to the land in a different way, we’re hoping that we’re going to grow those native plants in abundance, so that we can use them again in the way that they were meant to be used. It’s a tedious, time consuming, beautiful work of taking out plants that shouldn’t be here, invasive species that were introduced, and bringing back some of this delicate balance.

How can people support the Sogorea Te’ Land Trust?

If you live, work or play in our territory [including Alameda, Contra Costa, Solano, Napa and San Joaquin Counties], think about giving Shuumi. Shuumi in our language means a gift. It actually supports the work of Sogorea Te’. It gives us the ability to share this knowledge with many more people and to do the work of land return.

There’s a multitude of ways to get involved, and we are looking forward to making relationships. That’s really what Sogorea Te’ wants to do. We want to build relationships with people that are living in our territory so that we can all enjoy a beautiful place, where all of our children and grandchildren for the next seven generations can live in harmony with the land.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity. Visit Sogorea Te’ Land Trust’s website to stay connected. For more ways to support Indigenous communities and efforts to restore Native lands and foodways, see our list of Indigenous-led organizations in the Bay Area.

Topics: Environment, Food justice