Pastured Eggs: What it Really Takes

June 17, 2011

We spoke with two new pastured egg producers in the Ferry Plaza about the effort behind their products.

In the Central Valley, where Sara “Lynne” Hunt runs a small egg operation, the sight of chickens on pasture is enough to get people to pull off the road.

“People driving by will stop and ask, ‘What are those chickens doing running around outside?’” says Hunt, who has been raising hens under the name Shady Oak Organic Eggs in Turlock for around six months. “It’s been really interesting because I get to educate people, and explain how much better for you the eggs are when they come from pastured hens.”

Shady Oak is a side gig for Hunt at the moment, but one she feels very passionate about and hopes will one day become full-time. Currently, she spends about 20 hours a week caring for around 500 hens, on top of a full- time job as a real estate appraiser. “I’ve always been a farm girl,” she says, “but I didn’t realize what a difference organic practices can make.” She ties her recent interest in organic food to her spirituality, and she made some significant changes to both her diet and her outlook after reading a book called The Maker’s Diet. Now, she says, “I just really want to provide the best healthy eggs for my community.”

On top of what they eat on pasture, Hunt provides each bird with feed that includes organic, US-sourced grains and legumes, as well as flax seeds and kelp. Feed is her primary expense. “Those chickens are pigs!” she says. “I ration out their feed to three ounces a day for each hen.”

In addition to the long hours, Hunt was met with some significant challenges right off the bat. She had 80 chickens stolen, and although she has 200 new chicks, they’re not old enough to lay yet, so she doesn’t have enough eggs to meet the demand. She’s also lost several birds to coyotes and has recently moved them (and the small barn they sleep in) to a new, more protected piece of land owned by one of her farmers market clients.

Hunt won’t be appearing very often at the Ferry Plaza (her only farmers market for the time being), her business partner Carly Arnold runs the Thursday market stand. But she says she’s been really heartened to be welcomed into the market community when she has made the drive. She has no employees at the moment, but does get some help on the farm from her 20-year-old daughter Liz and her 3-year-old, Olivia, who serves as her “eggsecutive assistant” when it’s time to do the gathering.

Rolling Oaks Ranch (Tuesdays)

On a recent day at the market, Charlie Sowell was watching a portable office (like the kind you might see at a construction site) pass by on a trailer. “There goes one of my chicken houses,” he said. “Whenever I see one I wonder if someone is setting up a pastured egg operation.”

On a recent day at the market, Charlie Sowell was watching a portable office (like the kind you might see at a construction site) pass by on a trailer. “There goes one of my chicken houses,” he said. “Whenever I see one I wonder if someone is setting up a pastured egg operation.”

On the other hand, he knows he doesn’t honestly have much competition. And for good reason: Sowell and his girlfriend and business partner at Rolling Oaks Ranch, Liz Sorrow, have been working hard, non-stop, for the last several years; they opened a feed store in Ione around five years ago and, more recently, they’ve been producing pastured eggs, chicken and beef (around 25 cows a year) for a slow-but-steadily-growing group of customers.

Sowell and Sorrow fell into the egg business one day when a customer who had ordered day-old chicks called to say she couldn’t afford to pick them up. “By the end of the year I had 35 layers,” he recalls. “They started laying, I ate the eggs, and I thought, ‘Wow! They’re really delicious!’ So I started giving them away to family and friends.” Soon he was selling the eggs, and now he has around 1500 chickens.

Like Hunt, Sowell supplements his hens’ diet with feed made with US-grown grains — most of which are grown “as locally as possible.” (It’s his biggest production cost, and he estimates that they eat around 120 pounds of it a day). And, like Hunt, he says one of his biggest challenges is the hours. He can count on two hands the days he and Sorrow have taken off since they started producing eggs — including time off for funerals and a family wedding.

On top of the egg sales, Sowell also uses the market as a pick-up spot for beef customers. He sells whole and half animals up front, connects his customers to a butcher who will cut the meat as they like it, and stores it all in a walk-in freezer at the farm. This way, customers can pick it up at the market one cut at a time.

Sowell started selling at the Ferry Plaza last month (his second farmers market; he’s been at the Jack London Square Farmers Market in Oakland for around a year). Things are a little slow going now, but he doesn’t let that bother him. “The key is consistency,” he says. “And building real relationships.” Also important is explaining the real differences between pastured eggs and those raised in enclosed facilities — even those labeled “free range” — don’t necessarily come from birds that spend time outside. See more egg terms here.

Pastured eggs require more labor, a healthy pasture kept green with irrigation in the summer, much more space, and (because they get a lot more exercise) the hens eat almost as much feed as their indoor counterparts. Many of these costs account for a price difference that surprises some shoppers ($6-8 a dozen, versus $3-5).

“It’s frustrating to see commercial egg companies misleading the public, saying their eggs are ‘farm fresh.’ Sooner or later that will come to a head. I see the public becoming better and better educated, and pasture-raised eggs will be more of the norm than a rarity.”

***

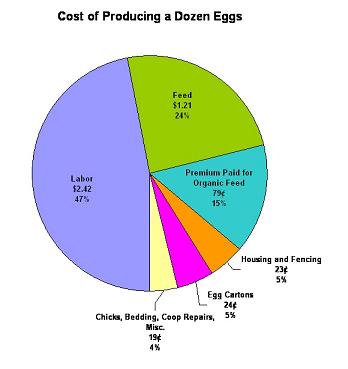

Below is a chart published by the folks at the Portland Farmers Market a few years back for an article called Cracking the Egg that details the cost to produce pasture-raised eggs.

Total direct production costs $5.08/dozen

Contribution to farm overhead $0.97/dozen

(rent, buildings, utilities, interest, etc.)

28% marketing fee (transportation to $2.35/dozen

market, farmers market fee, farmstand labor)

Total cost of production and marketing $8.40/dozen

Topics: Farmers, Meat/poultry