Inside America's Food Industry

Brie Mazurek, CUESA Staff

March 23, 2012

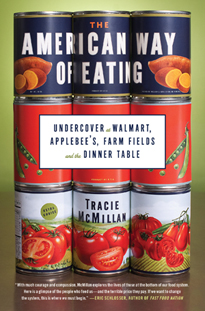

How do we make healthy food affordable for all, while improving conditions for the workers who produce, distribute, and serve it? CUESA recently invited journalist Tracie McMillan, author of the new book The American Way of Eating, to explore this question by sharing her experiences working undercover in the industrial food system. Adding her insight as a researcher of agricultural labor conditions and policy, Sandy Brown, co-owner of Swanton Berry Farm (the only organic farm in California to have a contract with UFW), interviewed McMillan before a full house of intent listeners at the Ferry Building’s Port Commission Hearing Room.

How do we make healthy food affordable for all, while improving conditions for the workers who produce, distribute, and serve it? CUESA recently invited journalist Tracie McMillan, author of the new book The American Way of Eating, to explore this question by sharing her experiences working undercover in the industrial food system. Adding her insight as a researcher of agricultural labor conditions and policy, Sandy Brown, co-owner of Swanton Berry Farm (the only organic farm in California to have a contract with UFW), interviewed McMillan before a full house of intent listeners at the Ferry Building’s Port Commission Hearing Room.

A self-described “working class transplant from Michigan,” McMillan got her journalistic start as a welfare and poverty reporter in New York. When assigned to cover a healthy cooking class at a public high school led by chef and activist Bryant Terry, she witnessed a transformation in how the students related to food. She was struck by a student named Vanessa, who was skeptical at first but eventually came around to the ideas presented in the class. Nonetheless, Vanessa still ate at her neighborhood Burger King several times a week. When McMillan asked her why she was still eating junk food after having learned a healthier way of eating, Vanessa responded, “This is what’s easy and affordable. If they want me to eat well, why is it so expensive?’”

Vanessa’s question eventually sent McMillan on a journey to explore food, class, and the forces that make junk food cheap and keep fruits and vegetables out of reach for many Americans. She set out to investigate the food industry from the inside, as one of its more than 20 million workers, many of whom are among the lowest paid in the country.

From Field to Plate

McMillan took jobs that would trace the story of food through three major channels of the corporate food chain: farm, retail, and restaurants. She harvested garlic, grapes, and peaches at farms in California. She stocked produce at Walmart (an empire that represents one-quarter of US food purchases), and she worked in the kitchen at Applebee’s (America’s most popular casual dining chain). She stayed at each job for two months and lived only on the wages she earned.

McMillan took jobs that would trace the story of food through three major channels of the corporate food chain: farm, retail, and restaurants. She harvested garlic, grapes, and peaches at farms in California. She stocked produce at Walmart (an empire that represents one-quarter of US food purchases), and she worked in the kitchen at Applebee’s (America’s most popular casual dining chain). She stayed at each job for two months and lived only on the wages she earned.

Though many people dismiss farm work as “unskilled” labor and justify low wages accordingly, McMillan felt challenged and humbled by her fellow workers’ skill and speed while cutting table grapes. At Applebee’s, however, she discovered that skill was largely taken out of the equation: much of the food arrived at the restaurant pre-cut, premade, precooked, and frozen, and the kitchen was more like an assembly line than a place where employees could develop culinary skills.

Due to the repetitive and manual nature of the work, injury was a regular occurrence in the jobs McMillan took. Cutting garlic in the Salinas Valley, she developed tendonitis and had to discontinue use of one of her arms. At Walmart, she witnessed workers wearing wrist braces due to repetitive strain from operating the price gun. “If you would like to hear a good approximation of machine gun fire, go to a Walmart at 1:00 in the morning,” she said.

Wage theft was also common. At Walmart she was asked to take three-hour unpaid breaks during the night shift to avoid overtime. Cutting grapes for piece rate on a team with two other workers, she discovered that her lack of skill brought all of their wages down, while at the garlic farm she made $16 for her first day’s harvest, though the company doctored her paycheck to make it look like she only worked two hours at minimum wage. And at Applebee’s, she was paid a lower hourly rate than she was promised when she was hired.

McMillan emphasized that her experiences were colored by her race, gender, education, and status as a US citizen, whereas the circumstances for most working poor, particularly immigrant farm workers, are much worse.

Bridging the Food Divide

While McMillan feels that her book provides “a framework for a discussion, as opposed to actual solutions,” she did offer some insights into to how we might mend this broken food system. To start, we must shift the conversation away from personal choice and toward deeper structural issues.

While McMillan feels that her book provides “a framework for a discussion, as opposed to actual solutions,” she did offer some insights into to how we might mend this broken food system. To start, we must shift the conversation away from personal choice and toward deeper structural issues.

“It’s easier to talk about what people are eating,” she said. “It’s a much heavier, more complicated discussion to look at subsidies and the [federal government’s] priorities in terms of public health and agricultural production.” She continued, “We only grow half the fruits and vegetables required for everyone to meet the recommended daily allowance.” McMillan proposed using public investment to ensure healthy food access for all and create alternative distribution channels for small producers and grocers.

Strengthening basic protections for workers through government regulation also ranks high in McMillan’s policy recommendations. She argued that paying food workers a fair wage isn’t at odds with making healthy food affordable: “All data suggests worker wages are a tiny part of the cost of food.” She pointed to the work of economist Philip Martin, who argues that if farmworker wages increased by 40 percent (from about $10,000 to $14,000 a year), the average American grocery bill would only increase by $16—annually.

As McMillan answered questions from the crowd, the discussion turned toward how we, as consumers, can identify and support businesses with responsible labor practices. In the restaurant industry, the Restaurant Opportunities Centers United offers a diner’s guide on the working conditions of American restaurants. Third-party certification programs, such as the Agricultural Justice Project, aim to create standards for social justice on farms. (Organic certification does not address wages or farmworker treatment.) “The fact that we have a rising domestic fair trade movement is a pretty nasty indictment of the state of labor regulation in the US,” McMillan pointed out.

While major policy changes are needed to establish a socially just food system, McMillan encouraged consumers to ask farmers, retailers, and restaurant owners about their labor practices in order to bring the issue to the fore. “Part of what has gotten people to support sustainable ag is talking to farmers and thinking of farmers as part of our communities,” she told the audience. “We should start trying to have those conversations about farmworkers and include them in the conversation.

Photos courtesy of Tracie McMillan.

Topics: Food access, Food policy, Labor, Talks