An Everlasting Meal

Brie Mazurek, CUESA Staff

July 20, 2012

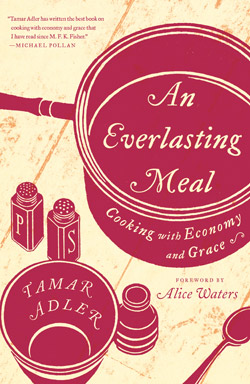

How do you make a meal last forever? Let the ending be a beginning: kale stems, chicken bones, and butts of stale bread all hold the potential for meals to come. It’s what writer, chef, and cooking teacher Tamar Adler poetically refers to as “catching your tail” in her book The Everlasting Meal: Cooking with Economy and Grace.

How do you make a meal last forever? Let the ending be a beginning: kale stems, chicken bones, and butts of stale bread all hold the potential for meals to come. It’s what writer, chef, and cooking teacher Tamar Adler poetically refers to as “catching your tail” in her book The Everlasting Meal: Cooking with Economy and Grace.

Adler earned her chef stripes at Chez Panisse and other restaurant kitchens, but she does not expect home cooks to have the skills of a professional chef. She encourages us to start where we are, with whatever happens to be in the fridge and pantry. In 20 essays peppered lightly with recipes, she explores the pleasures and limitless possibilities of cooking simply and intuitively, with an emphasis on keeping waste to a minimum, getting the most out of good ingredients, and saving kitchen mishaps from the compost bin.

At CUESA, we know that affordability is as much as a concern for eaters as economic viability is for farmers, and both are essential ingredients in a healthy food system. We talked with Adler about how kitchen confidence can help home cooks make better food choices without breaking the bank, and how salvaging those castoff kale stems can be an act of grace.

CUESA: You say you modeled your book after M.F.K. Fisher’s How to Cook a Wolf, which was written in a time of wartime shortage. What inspired you to focus on resourcefulness and economy today?

Tamar Adler: When I started writing the book, it was a precipitous time. I was living in the Bay Area, and I felt and heard around me a sense of real tension between people wanting to eat responsibly and the realities of our economy in 2008 and 2009. Everywhere, I was seeing all of this well-founded, absolutely necessary data about how damaging our industrial food system is to our democracy and social and environmental ecologies. At the same time, all of the advice for dealing with eating on a dime was in complete polar relationship to that. Half of the new websites were about how important it was to eat grass-fed beef and local peaches and spend more money on food because we need to eat real food, and the other half were about 10-cents-a-day tricks for eating lunch, which involved going to Costco and buying juice concentrate and discount meat. I felt like these pieces didn’t hold up to each other.

Tamar Adler: When I started writing the book, it was a precipitous time. I was living in the Bay Area, and I felt and heard around me a sense of real tension between people wanting to eat responsibly and the realities of our economy in 2008 and 2009. Everywhere, I was seeing all of this well-founded, absolutely necessary data about how damaging our industrial food system is to our democracy and social and environmental ecologies. At the same time, all of the advice for dealing with eating on a dime was in complete polar relationship to that. Half of the new websites were about how important it was to eat grass-fed beef and local peaches and spend more money on food because we need to eat real food, and the other half were about 10-cents-a-day tricks for eating lunch, which involved going to Costco and buying juice concentrate and discount meat. I felt like these pieces didn’t hold up to each other.

The thing that drove me to start writing was that those two things are not in opposition to each other at all. They actually rely on each other. Eating responsibly in a social and emotional and environmental way and eating resourcefully in a financial way are completely interdependent. That was the opposite of what everyone was being made to believe.

CUESA: Much has been said about why we should support sustainable agriculture. This seems to be implicit in your book, without being didactic. How can we help more people think in these terms?

TA: You can’t start with the better ingredients. You have to start with cooking. I lived there in the heart of it [in the Bay Area], and I watched people struggle with the fact that the kale they got at the farmers market cost as much or more, and came with its stems and bugs still on it, than the kale they got at Trader Joe’s, which was washed and already cut. I watched them hold $6-a-pound pastured ground beef, and then hold 99¢-a-pound ground beef and say, “This does not make sense.”

Absent an understanding of the real cost of food, it didn’t make sense for them. But that’s because they didn’t know what to do with the stems of the kale or the cooked kale. They didn’t know how well vegetables with higher micronutrient content hold up to being cooked ahead, and how different they feel in one’s body. When it came to the beef, if the way you deal with ground beef is making a burger, I understand why $6 a pound doesn’t make sense. If you understand that by making a sauce with ground beef, you actually turn it into many more meals, meals that feel more diverse and more elegant and more exotic than a burger, suddenly the better meat starts to make sense.

I didn’t think it would be useful for me to tell people what to buy. I thought that if I could explain to people how to cook, then, and only then, could they begin to justify making the decisions that they would want to make.

CUESA: The subtitle of your book is Cooking with Economy and Grace. How are those two things connected in your mind?

TA: Grace is a word that has really fallen out of use. Other than in the liturgy, we don’t talk about grace very much, and I wonder if that isn’t because there is a certain amount of reserve to grace. There is a certain sense in which grace involves not always wanting and striving but actually positioning oneself in a less consumerist and less consuming relationship to the world around one. We’ve begun to define our participation in society so much in terms that are largely about obtaining, having, or keeping that the word grace has lost some of its relevance. I wanted to breathe life into it through a perspective on food and life that actually prioritizes treating things carefully and resourcefully.

TA: Grace is a word that has really fallen out of use. Other than in the liturgy, we don’t talk about grace very much, and I wonder if that isn’t because there is a certain amount of reserve to grace. There is a certain sense in which grace involves not always wanting and striving but actually positioning oneself in a less consumerist and less consuming relationship to the world around one. We’ve begun to define our participation in society so much in terms that are largely about obtaining, having, or keeping that the word grace has lost some of its relevance. I wanted to breathe life into it through a perspective on food and life that actually prioritizes treating things carefully and resourcefully.

Learn more about The Everlasting Meal on Tamar Adler’s website. Turnips photo by Olivia Sargeant. Tamar Adler photo by Dan Kim.